When the winner of the U.S. Amateur championship was announced in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle on November 8, 1945, there was an interesting article on the front page about 48-year old James McPhelan, a Brooklyn policeman who, after being questioned all night, was arrested for homicide for shooting a civilian the night before.

Off duty and in civilian clothes, he saw the victim standing near a parked car and acting suspiciously. When McPhelan approached the man he ran down the street and ignored orders to stop. That's when the policeman drew his revolver and fired five shots, one of which went through the victim's back and out his chest. The victim managed to reach the door of his apartment before he collapsed and died. According to the Police Surgeon, the officer was unfit for duty. Except for a couple of details, the story sounds strangely modern.

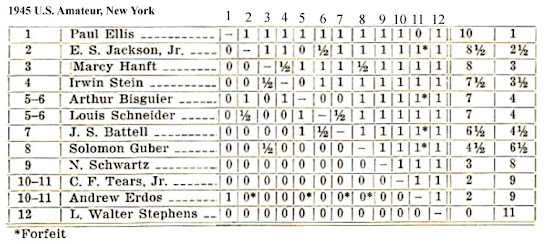

The winner of the 1945 U. S. Amateur Championship which was held in October and November at the Marshall and Manhattan Chess Clubs was a virtually unknown and apparently true amateur player named Paul R. Ellis from the The Bronx, New York.

The event was described as one of the most exciting races of recent years and Ellis' performance prompted Chess Review to make the bold statement that he might be a candidate for the next U.S. Championship. That's because he had breezed through the Preliminaries and his 10-1 score in the finals was equally convincing.

Ellis learned to play chess at the age of 12 from neighborhood kids and in 1932 he captained the his high school team to the New York

Commerce Interscholastic championship, but didn't play any serious chess during his City College days.

However, between 1933 and 1936 he played for the Empire City Chess Club team in the Metropolitan Chess League matches. During those years he excelled, defeating players of the caliber of, among others, Arnold Denker and Abraham Kupchik.

After a layoff of almost ten years during which time he played no tournament chess, he picked up a stray copy of Chess Review magazine, saw the tournament advertised and decided to enter even though he was without any preparation and was unfamiliar with the most recent opening analysis.

Style-wise his play was positional, he was tenacious in difficult positions and he played the ending well. Apparently Ellis soon disappeared from the chess scene.

In the following critical game Ellis defeated Edward S. Jackson Jr., the defending champion. In this tournament 16-year old Arthur

Bisguier made a very favorable impression and one of his wins was selected by Reuben Fine for Chess Review's Game of the Month.

In this game which featured a four Rook ending, Jackson needed a win in order to retain the title and the win was there, but he missed it.

Once upon a time I studied two books on endings: Basic Chess Endings by Reuben Fine and The Endings in Modern Theory and Practice by Peter Griffiths.

I still have the latter book and it's filled with notes penciled in the margin. If you can find a copy and are interested in really studying the endgame, it's still a valuable book.

In it Griffiths did not devote a lot of space to four Rook endings, saying that in many cases they are more complicated cases of single Rook ending.

Although there is not a lot of material available on endings with four Rook they do appear frequently and they are different.

The "rule" is that four Rook endings are drawn with two exceptions. One, a mating attack is possible and two, you can exchange a pair of Rooks leaving you with a won R+P ending.

[Event "U.S. Amateur, New York"]

[Site "?"]

[Date "1945.??.??"]

[Round "?"]

[White "E.S. Jackson, Jr."]

[Black "Paul R. Ellis"]

[Result "1-0"]

[ECO "B72"]

[Annotator "Stockfish 156"]

[PlyCount "106"]

[EventDate "1945.??.??"]

[SourceVersionDate "2022.11.16"]

{Sicilian Dragon} 1. e4 c5 2. Nf3 d6 3. d4 cxd4 4. Nxd4 Nf6 5. Nc3 g6 6. Be2

Bg7 7. Be3 O-O 8. Nb3 Nc6 9. f4 Be6 10. g4 {Jackson was a very aggressive

player so this line suits him very well.} Na5 {This is not good. Much better

was Botvinnik's 10...d5} (10... d5 11. f5 Bc8 12. exd5 Nb4 13. d6 Qxd6 14. Bc5

Qf4 15. Rf1 Qxh2 16. Bxb4 Nxg4 17. Bxg4 Qg3+ 18. Rf2 Qg1+ 19. Rf1 Qg3+ 20. Rf2

Qg1+ {Draw agreed. Alekhine,A-Botvinnik,M Nottingham 1936}) 11. g5 Nd7 12. Qd2

Nc4 {In Motwani,P (2425) -Mestel,A (2515) Swansea 1987, black played 12...Rc8}

13. Bxc4 Bxc4 14. O-O-O Bxb3 (14... Rc8 {is also reasonable.} 15. Kb1 Bxb3 16.

axb3 Bxc3 17. bxc3 Nc5 {Equal. Fiori,H (2081)-Rodriguez,J (2406) Buenos Aires

2014}) 15. axb3 Qa5 {This threatens ...Qa1+ but has the additional advantage

of preventing the advance of white's e-Pawn.} 16. Kb1 Rfc8 {Considering the

N's coming activity the best course of action was to eliminate it with 18...

Bxc3} (16... Bxc3 17. bxc3 Nc5 18. Bxc5 dxc5 19. h4 {with approximate equality.

}) 17. Bd4 {Black is in a difficult position here. If he allows the exchange

of Bs white has a strong attack. The move he played has the disadvantage of

leaving him weak on the d-file.} e5 (17... Bxd4 18. Qxd4 Rc6 19. b4 Qb6 20. Qd3

e6 21. b5 Rc7 22. Qxd6) 18. fxe5 Nxe5 19. Rhf1 Rc6 20. Nd5 Qxd2 21. Rxd2 Re8

22. Nf6+ {What could be more reasonable than this? Still, he should have

grabbed the a-Pawn which would have left him with a significant advantage.}

Bxf6 23. Rxf6 b6 {Black has pretty much managed to equalize here.} 24. h3 (24.

Bc3 {According to an old note by Kmoch this virtually leaves black without a

move. but that's an overstatement. While his position is difficult, black can

keep himself in the game with 24...Nd7} Nd7 25. Rfxd6 Rxd6 26. Rxd6 Nc5 27. Bd4

Nxe4 28. Rd7 Nxg5 29. Rxa7 b5 {Now comes white's only move to hold any chances

of winning.} 30. c4 b4 31. Ra4 Nf3 32. Bb6 {White's advantage is minimal and

Shootouts indicate that a draw would be a reasonable outcome.}) 24... Nd7 {

There is not much going on in this position and the maneuvering that follows

is not difficult to understand.} 25. Rf4 Nf8 26. Rg4 Ne6 27. Bf6 Nc5 28. Rd4

Nd7 29. Rf4 Re6 30. b4 h6 31. h4 Nxf6 32. gxf6 {[%mdl 4096]} (32. Rxf6 {

was more accurate.} hxg5 33. Rxe6 fxe6 34. hxg5 {This position should be drawn.

}) 32... Kh7 33. c3 g5 34. hxg5 hxg5 35. Rf5 Kg6 36. Rdd5 {Correct was 36.Kc2}

(36. Kc2 Re5 (36... Rxe4 {is safely met by} 37. Rxg5+ Kxg5 38. Rxe4 Kxf6 39.

Re1 {and white can hold the draw by marching his K over to the K-side.}) 37.

Rxd6 Rxd6 38. Rxe5 Rxf6 {Black has the better chances.}) 36... Rxe4 {Missing

the win.} (36... Re5 {leaves white with no good options.} 37. Kc2 (37. Rfxe5

dxe5 38. Rxe5 Rxf6 {wins.}) 37... Rxf5 38. Rxf5 Rc8 39. Kd3 Re8 40. Ke3 Re6 41.

Kf3 Rxf6 {wins}) 37. Rxg5+ Kxf6 38. Rg8 Ke6 39. Rh5 Rc7 40. Kc2 {This should

have lost a P, but even if black had captured on b4 it probably would not have

been sufficient to win the game,} Re5 {Missing the win of a P with 40...Rxb4.

Even then, even though he two Ps up, has an outside passed P and white's K is

far away the two active white Rs would make the win unlikely. Keep in mind the

curious pin on the c-Pawn...it will play a part later!} 41. Rh4 d5 42. Kd3 Rf5

43. Rg3 Kd6 44. Re3 Rf2 45. b3 Rb2 46. Rh6+ Kd7 47. Rh7 Kd6 48. Rf3 Rxb3 {

All this R maneuvering has resulted in a position where black has a clear

advantage, but because of the double Rs it's only a draw...if white finds the

one move here that does not lose.} 49. Rfxf7 {[%mdl 8192]} (49. Kc2 Rxb4 {

wins the b-Pan and this time it's enough to give black the win.}) (49. Rhxf7

Rbxc3+ 50. Kd2 Rxf3 51. Rxf3 Rc4 {Black has a won ending.}) (49. Rh6+ {This is

the only mover that holds the draw.} Ke5 50. Rh5+ Kd6 51. Rh6+ {draws by

repetition because retreating to the 7th rank does not help black's cause

either...} Ke7 52. Rxf7+ Kxf7 53. Rh7+ Ke6 54. Rxc7 Ra3 55. Rh7 {and black can

make no headway.}) 49... Rbxc3+ {After this black is two Ps up plus he can

eliminate a pair of Rs leaving him with a won R+P ending.} 50. Ke2 Rxf7 51.

Rxf7 Rb3 52. Rf4 Ke5 53. Rh4 d4 {[%mdl 32768] White resigned.} (53... d4 54. b5

Kd5 (54... Rxb5 55. Rh5+) 55. Rh7 Rxb5 56. Rxa7 {This ending can be a bit

tricky, but for white, playing on would ultimately prove futile.}) 1-0

No comments:

Post a Comment